Redwood Cathedrals

Beyond the Christmas Tree

We offer Fire Philosophy as a space for living questions—for Nietzsche’s provocations, Zen’s paradoxes and silences, and the uneasy beauty of learning how to live with courage and imagination.

We offer this free of charge. But if you find value in our brief essays, video interviews and dialogues that challenge and unsettle our lives while nourishing and invigorating them, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or sharing us with others. Your support keeps stoking our collective 🔥.

~ Krzysztof and Dale

December, 2025: For those of us who share this cultural background, it is the season of the Christmas tree, conifers harvested on northern tree farms and shipped off to our living rooms. The fragrance is wonderful, and the memories evoked—fabulous for many of us. Recently, however, what this custom brings to my mind is the fate of the giant of all conifers, the monarch of all trees. Because if there is one plant on the planet that invariably inspires awe, a sense of grandeur and majesty, and a reflective response of humility and reverence—it would surely be the redwood tree. At least, that’s been true for me my entire life and these feelings have never been diminished no matter how frequently I visit the giant trees.

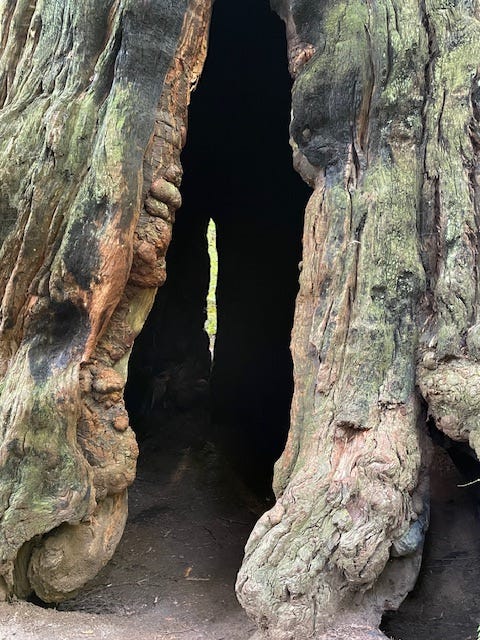

When I first saw redwood trees as a child I was awed by their enormity, their sheer unclimb-ability, and from then on, I was continually mesmerized. I couldn’t keep my eyes and my hands off them. They overpowered me but less through intimidation than through a sense of timeless, wise oversight. These trees are living beings, just like me, but ancient, sometimes thousands of years old, weighing thousands of tons, simply overwhelming in the power and grandeur of their presence. Burrowing down into the earth and from there ascending high into the heavens, they are cathedrals of unmatched majesty. No human-built temple no matter how magnificent could ever inspire the kind of reverence that these natural divinities do for me.

Just picture one of these giants. A redwood trunk can be up to 30 feet in side-to-side diameter. Its footprint sits on the ground like a small house of 700 square feet, with a walk-around circumference of up to 100 feet. But unlike a house, a giant redwood soars into the air like a 35-40 story skyscraper. Stand a football field up on its endzones and you’re still dwarfed by these giant trees. Standing down under a redwood tree there is no perspective that allows you to see its top. Perfectly erect, it is often the case that a redwood’s first substantial branch is well over 200 feet above the ground, just over halfway to the top canopy and spire. The tallest existing redwoods reach up to 380 feet, but we know very well that some of the trees logged in the 19th century were even taller. In our now deeply regretted ignorance and greed, we human beings logged trees more magnificent than any now living on the earth. And we just kept on logging these irreplaceable forests until they neared extinction.

The redwood’s size is a ponderous mystery: How is it possible that something so tall and so heavy could stand there upright through all weather conditions of severe wind and storm for thousands of years? All we can say is that they manage that through teamwork on the one hand and through graceful, flexible movement on the other. In wind and storm the trees in a redwood grove all chant together in deep base tones, stretching, bending, and flexing with the flow of other earthly conditions to create their own choral arrangement. They dance and sway together in perfect harmony and mutual support. As Lao Tzu teaches us in the Tao Te Ching: “Plants are born tender and pliant; dead, they are brittle and dry…. The hard and stiff will be broken. The soft and supple will prevail.” Through extremely thick fibrous bark and in the incomparable wood there is nothing rigid and breakable; their strength is astonishing.

By the best estimates, there were over 2 million acres of old growth redwoods in California before the arrival of European-American loggers. While early handsaws and axes were a meager match for a giant redwood tree, they were quickly surpassed by bulky steam powered saws before gas chainsaws accelerated the pace of destruction. Over the subsequent century and a half of logging only 4% of the old growth forests would be left standing. 96% of these magnificent trees were harvested for lumber, and unlike other trees that can be farmed, harvested and replanted, the replacement timeline for an old growth redwood is measured not in decades but in thousands of years. The redwood floor joists and infrastructure in my 1926 Spanish style home in Los Angeles are a fragmented reminder of this destruction. It is estimated that there are now only 90,000 old growth redwood trees still standing—the 4%—now mostly protected within the borders of state and national parks.

Redwood fueled the industrial expansion of the US, building everything from Bridges to railroad ties to office buildings and homes. Redwood lumber is largely free of knots, light but incredibly strong. Its deep red color is mesmerizingly beautiful. It doesn’t decompose like other wood, resisting all forms of decay for decades, even centuries. Redwood resists termites and all other kinds of bothersome pests. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect material out of which the US could be constructed in its heyday of building. The old pine forests that served as the primary building material for the East coast construction boom could produce up to 30,000 board feet of lumber per acre. But even one reasonably large redwood tree could produce up to 8 times that amount of wood—one tree! And once twentieth century logging technology was on the scene, a whole forest of redwood trees could be monetized into an astonishing fortune in a matter of months. At the height of industrial capitalism, this was all the motive it would take to clearcut the world’s most primordial and awe-inspiring forests.

Given how we modern human beings understand our relation to the natural world, nothing in our pasts would stop the profiteering from these incredibly valuable trees. We can now see in retrospect that the horror of the redwood’s rapid elimination didn’t dawn on anyone as an issue until a few early conservationists began to notice what was already lost. The Save-the-Redwoods League was formed in 1918 and money was sought to purchase some small portion of old growth trees before it was too late. John D. Rockefeller was prominent among the wealthy donors, and when the Rockefeller Grove was christened in Humboldt State Redwood Park, the Rockefeller family was there in royal attendance. There are revealing photos of the ceremonial banquet under the giant trees with lavish pure white tablecloths, the finest china, and exquisite cuisine right there in the darkened shade of these giant trees. Finally, in 1968 Congress acted to establish the Redwood National Park, by then a patchwork of scattered groves amid miles of already logged hills. By then the damage was monumental and the loss unrecoverable. All we can now say is that at least a palpable reminder of the magnificence of these ancient forests had been saved.

There are two types of redwood trees in California (and another in a remote region of China). The California coastal redwood grows in small valleys and mountainsides along the coast from Big Sur in the south up to and just across the Oregon border. These trees reject direct salt air and therefore tend to avoid the mile or two closest to the ocean. But they flourish in the moist foggy weather that only exists within the first ten miles of the Pacific coast. This narrow band along the Northern California coast is the sole domain of the coast redwood tree.

The other redwood trees are concentrated on the western slopes of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains, most notably in Sequoia National Park. Called the Giant Sequoia, these enormous trees get their water from snow melt and thrive in the otherwise dry conditions of Southern California. The General Sherman Tree in Sequoia National Park is the largest living thing on the planet in terms of sheer mass. It stands at 275 feet in height with almost unimaginable bulk at its base. The coast redwoods are taller than the giant sequoias, sometimes as much as 100 feet taller, but their trunks are not as wide in diameter, making them slightly less imposing to someone standing on the ground. For utter magnificence, though it would be hard to choose between these two types.

Redwood trees need sunlight to grow and when they get it, they grow quickly, adding mass more and more rapidly. A redwood tree in good circumstances of sun and water can grow to a massive size in 500 years. But that’s still its adolescence. It may not stop growing taller until it is a thousand years old, and after that it may add significant bulk without pushing higher into the sky. Often a young redwood is so thoroughly shaded by the redwood canopy of other trees that it sits in the dark year-round. Although this would kill other trees, a redwood can live comfortably in total shade, waiting even hundreds of years for its chance to begin growing. When another giant redwood above it crashes to the earth or when a lightning strike fire opens the canopy above it for sunlight to penetrate, its life of ascension begins. Given an opportunity, a previously dormant redwood leaps into action, reaching for the light at breakneck speed.

The shade gardens in coastal redwood groves are mysterious places of darkness even on the brightest days of sun. Often the only plant life surrounding the trees are ferns and clover that can exist with almost no light. One of my family’s favorite camping stories occurred in the darkness of a redwood grove in Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park. Having driven what to a child’s mind seemed like an endless day to get there, we drove into the campground to select a camp site. Lanterns were lit in the other campsites and fires burning in fire pits for illumination. Worn out by the drive my parents assumed from the utter darkness that night had fallen, and promptly put my sisters and I to bed once the tent had been erected. Maybe a half hour later my mother looked at her watch—it was 4:30 in the afternoon even though pitch dark under cloudy skies and the thick redwood canopy. To our utter astonishment and joy, we children were liberated from our sleeping bags with great hilarity and played for hours under these giant trees with our flashlights. The redwood canopy had enabled a total solar eclipse.

The depth of this darkness is caused both by the enormous height and size of these trees and by the extent of their luxurious canopies growing hundreds of feet in the air. In addition to the redwood’s own branches, needles, and seeds, there are plants and animals of many varieties living hundreds of feet up in the air, most of them unable to survive in the dark under-gardens. Mosses, lichens, and ferns thrive, along with huckleberries and other plants deposited in the defecated remains of birds. Epiphytes—plants that grow on other plants—exist in great variety in these elevated sky palaces. Enormous redwood branches collect pockets of soil several feet deep that grow over time through decomposition up there hundreds of feet in the air.

Botanists and zoologists who now climb up into these high elevations claim that, with the exception of the deepest areas of ocean, these high redwood canopies are the last frontier of botanical exploration. They claim that nowhere else on earth can soil from decomposition be found in such quantities so high up off the earth. And now for the first time due to advances in tree climbing technology and expertise, the redwood forest canopy is open for biological exploration. These scientists had come to realize that the only way to thoroughly study and understand a redwood tree was to climb it. The trees themselves feed on rainwater that is captured in the high canopies. In addition to water sucked up through their extensive root system to be siphoned hundreds of feet up through the trunk over several weeks’ time, redwoods can absorb water through their needles high up in their canopies, reversing the natural botanical flow by using gravity to help send rainwater down into the tree.

Astonishingly, there are still redwood groves being discovered in a few thick unnavigable forests of these several parks in Northern California. Some sections of this terrain are so steep and so densely overgrown that it is virtually impossible to get there. When a new redwood grove is discovered, the explorers—mostly dedicated botanists—maintain secrecy about its location so that curious redwood tourists don’t ruin the growth conditions for these trees. The exact location of the Atlas Grove in Prairie Creek Redwoods Park, for example, considered by many tree experts to be the “Sistine Chapel of the world’s forests,” is known only to a few devoted worshippers.

Surprisingly, the roots of a redwood tree don’t dig as deeply into the earth for support as we might expect. Instead, they spread out widely, well over 100 feet in all directions. It’s as though a 300-foot tree sits on a flat platter for support, but a platter that is interwoven with other tall trees so that no tree stands alone, having joined roots with other trees in the vicinity. Redwood trees don’t die in a standing posture as most trees do. Instead, as living beings, they fall to the ground in an earthquake level jolt destroying everything in their path, and then continue living on the ground for some period of time. Even though conditions on the ground are dark and moist, redwoods are so massive and their wood so resistant to decomposition that it takes centuries for them to return to the earth. Your redwood deck will probably outlive you.

We can now realize—if we are attentive enough—that, like tragic deforestation in the Amazon River basin, the loss of the planet’s redwood forests is an incalculable tragedy. We are only now becoming aware of the loss—not just our loss but the planet’s loss—precisely in the loss of it. The tragedy that occurs with every extinction is that “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone.” That the cultural motive for this devastation has been our greed, our hasty grabbing for immediate wealth, doubles the sense of tragedy. The shame of that realization overwhelms me. Have we learned enough not to repeat this devastation? Doubtful. That would require a fundamental shift in our relation to the natural world and a profound alteration of our ways of living through a mental/spiritual revolution.

We would need to learn to co-operate with the world around us, not dominate it by treating all relations to the earth as mining. We would need to abandon our arrogant sense of self-sufficiency and to stand in awe of the natural world that has given rise to us—reverence to our ancestors.

The encouragement to do this is simple—it stands there facing us as the single condition placed on our own survival. Not just ignorant overexploitation of limited resources on the earth but willfully blind continuation of these destructive practices. In view of this devastation, it is important that we cultivate a sense of the importance of these trees, important that we now cultivate a reverential appreciation of the remaining redwoods along with all other forests. For me, that’s not at all difficult.

It is not difficult because the minute I wander into the redwood grove my state of awareness is immediately altered. I listen, look, smell and touch a very different world, and my mind is open and alive in a way that it had not been minutes before. As I meander along, I feel the deep quiet inside myself, seeping in from all around me. I can viscerally sense my own evolution out of this rich, moist darkness of the earth. I have discovered somewhat to my surprise that in certain states of mental openness in this setting I can feel literally embraced and encompassed by the natural world.

Entering a redwood grove people just instinctively go quiet. Encountering other people hiking in the redwoods, rarely do I hear the usual chatter. People seem compelled to silence. The profound stillness in redwood groves compounds the sense of sacred space, a space in which reverence is evoked in almost everyone regardless of religious heritage or lack thereof. If, as I do, you thought it important to reimagine the spiritual dimension of human life, you would find no better symbol of that depth dimension of life than a grove of redwood trees. If sacred space has a symbol in the natural world, these profound redwood sanctuaries are surely it.

Krzysztof here: If you are at all inspired by Dale’s reflections above, you should run, not walk, to read Richard Powers’s wonder-inspiring book The Overstory.