Moral and Intellectual Courage: Part III

In this third post on the topic of courage, I combine what could be considered two closely related forms—those of moral and intellectual courage. Courageous moral acts make a stand against injustice where holding that position entails great risk.

Courageous intellectual acts also take personal risks but do so in order to explore and embrace ideas that are out of conformity with prevailing opinion in their communities. We can think of both of these as the substantial courage it takes to truly be yourself—sometimes all alone— in some degree of opposition to others around you, especially where that means figures of authority and power. But best to consider these courageous individuals to be those who take a personal stand not so much against people as against the social and psychological forces of injustice and dogmatism that surround us.

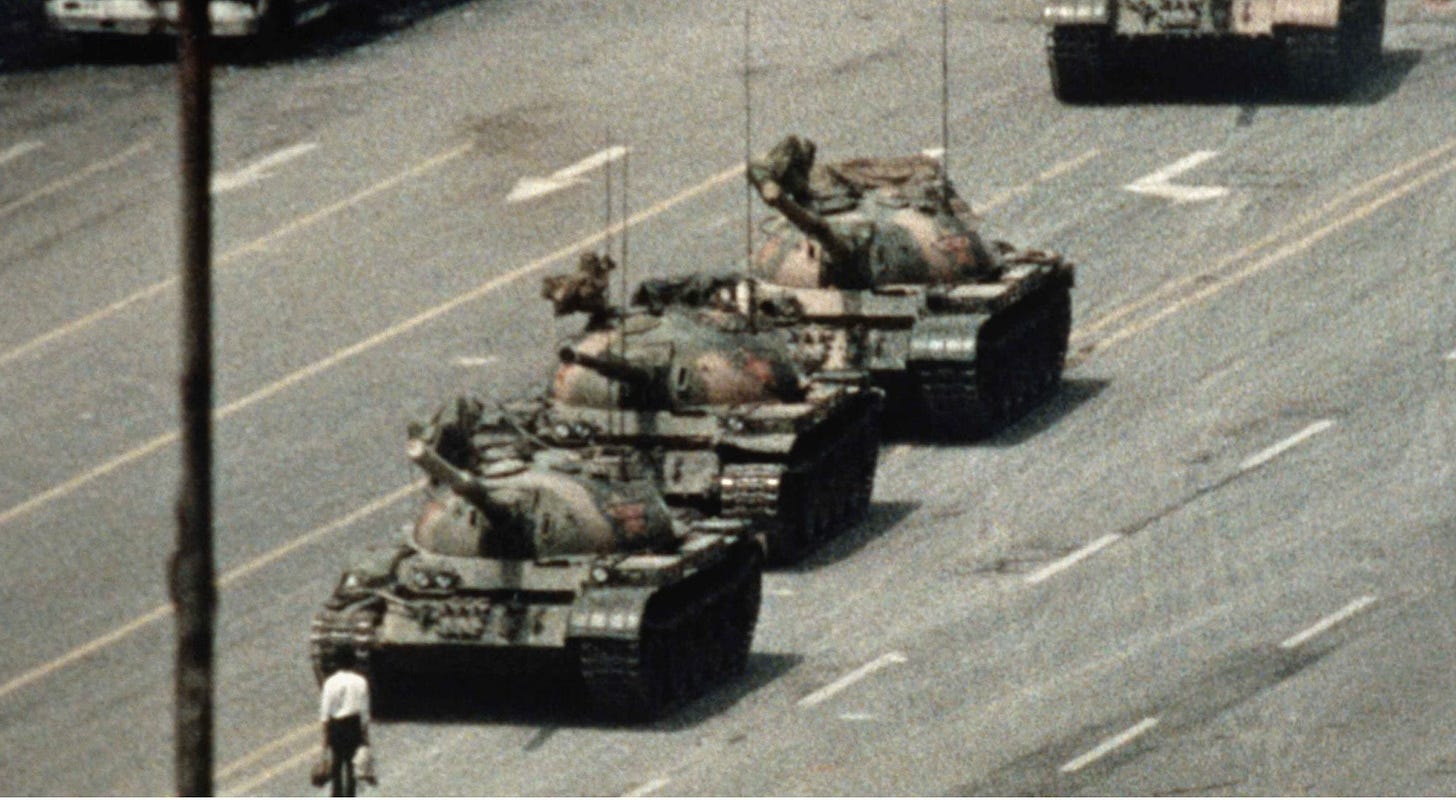

We’re all familiar with those who show moral courage, those who speak up for what’s fair and just, what’s right, even when there are great risks in taking such a stand. This courage is startling when we see pure examples of it—the capacity to respond to injustice with determination even when assuming that level of responsibility may entail enormous personal risk. Beyond physical bravery, this form of courage shows inner strength, deep resolve, and commitment to a principled life.

Courage with a deep moral quality always results from a transformation or maturation of character. This change entails a movement from seeking to benefit ourselves to seeking something beyond our personal interests, something important on behalf of others or on behalf of values that we all share. This movement brings about an impressive form of growth, an expansion of the range of our striving, the range of who we are.

Those of us who are morally weak or underdeveloped can only pursue our own benefit, and the longer we engage in this confinement of self-absorption the more we diminish ourselves by implanting that small-minded reticence as a habit.

For this reason, actualizing this form of courage in real life situations requires some level of detachment from our personal sense of self-importance. It requires the capacity to see who we are with clarity and to recognize that there are levels of importance far beyond our own.

We have many impressive exemplars of moral courage, perhaps the best known of which are Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks who both demonstrated enormous strength and determination in the face of hatred and violence. Refusing to remain silent and acquiescent under the weight of oppression and injustice, they voluntarily faced dangers and risk that few of us ever encounter. As they both claimed, their courage was definitely not the absence of fear, but rather the resolve to act in spite of fear on behalf of the principles of justice and love. Although committed to nonviolent means, their courage was far from passive. On the contrary, the moral stands they took sought to confront hatred and violence directly without themselves becoming hateful and violent.

Here is another example of moral courage, less known but possibly just as historically significant. Tarana Burke’s moral courage inspired the “Me too” movement. Although, like Burke, many others in her community had experienced sexual violence in the Bronx and the 1970s and 80s, violent threats of retaliation had prevented them from reporting or speaking out in response to their mental and physical injuries. But Tarana Burke resisted this suppression, speaking out forcefully with moral courage and

conviction in spite of constant verbal and physical abuse. Telling the stories of her own traumatic experiences, she devoted her life to helping other women in her predominately black community through these personal crises. A full decade later women in Hollywood adopted Burke’s “Me too” cry in response to Harvey Weinstein’s horrendous record of violent sexual abuse. While “Me too” then went viral all over the world, Burke focussed less on the sexual scandals that were being exposed and much more on helping women share their experiences for the purpose of rejuvenation and healing. Burke’s moral courage was and is extraordinary. Making her heroic stand paved the way for significant cultural change.

Intellectual courage is somewhat similar to moral courage in that it entails challenging ourselves and others. It requires the personal capacity to question old habits of thought that have governed our thinking and to reach out into new ideas. It is the courage to let go of illusions, no matter how comforting. It faces up to the fear of change by continuing to pursue the truth wherever that leads no matter how personally uncomfortable that may be. This courage requires the mental lucidity and determination to challenge one’s own beliefs and be willing to let intellectual exploration change one’s mind and one’s life. To some considerable degree at least, it demands that we learn how to live without the comfort of believing that we already possess the truth.

Like moral courage, intellectual courage is linked to the urge for inner growth, for the enlargement of mind and character. Leaders of the European “age of enlightenment” understood this demand clearly, along with the realization that some element of risk was always involved in change. Therefore, Immanuel Kant’s motto was Aude sapere—”dare to know,” dare to risk the personal and social transformations that the pursuit of truth will invariably entail. As Nietzsche wrote in his “Attempt at a Self-Criticism:

How I regret now that in those days I still lacked the courage…to permit myself in every way an individual language of my own for such individual views… (Birth of Tragedy, sec 6)

But in retrospect we can see that even before this self-critical note of honest self-appraisal Nietzsche was already on his way to becoming one of our foremost exemplars of intellectual courage.

What is it that sparks the courage of open minded imagination? What inspires the courage of free thinking, the courage to pursue an extra-ordinary way of looking at reality? The Bible claims that “Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Proverbs 9:10) which is to say that fear of consequences will inspire you to wise up. We all sense how fear of punishment for being wrong or for being deviant motivates obedience to traditional commandments and cultural boundaries. This is the wisdom of conformity, the wisdom of keeping yourself in alignment with the established values of your community. We should not belittle this form of wisdom. But in contrast to this claim about the origins of wisdom is one coming from Plato and Aristotle that “philosophy begins in wonder.” Their point is that wonder and awe give rise to the initial spark of inquiry and that perplexity, imaginative exploration and resolute questioning provide a path to wisdom. This is the wisdom of intellectual courage and it can sometimes force you to be uncomfortably out of alignment with your community.

Perhaps our most famous example of intellectual courage comes from Galileo, the 17th century Italian scientist and inventor. Galileo came to be convinced that his observations confirmed Copernican heliocentrism—the view that the sun was the center of our cosmos. This idea was starkly opposed to the Biblical and common sense idea about the centrality of the earth. Standing firm to his pursuit of the truth, Galileo provided arguments for his view to the Pope, the church, and other scientists. He knew, of course, that this matter wasn’t “strictly academic,” and that he would be taking life threatening risks to espouse a different view. Galileo was tried by the Inquisition, found guilty of heresy, and spent the remainder of his life under house arrest. “This takes courage.”

If you found value in reading about courage, consider supporting Fire Philosophy by becoming a paying member or giving a gift subscription to a friend who could use some courage in the face of adversity.